INTRODUCTION

HOW PAVEMENT HELPED CREATE THE MODERN CITY

In the 19th century, paving city streets was considered the most important civic improvement for the modernization of American cities, along with the installation of sewer systems. With the exception of a few streets in the older port cities along the east coast, dirt streets were the norm, both downtown and in residential areas. In dry periods, dirt streets generated dust, while with rain they could often become impassable quagmires, which posed threats to people’s health and inhibited the effectiveness of firefighting vehicles. “Paved streets are inseparable from municipal progress,” as Savannah Mayor Herman Myers stated in 1896.[1] This sentiment was felt by municipal officials across the country. But how best to pave streets was no easy answer, resulting in a remarkable variety of types of pavement even within a single city.

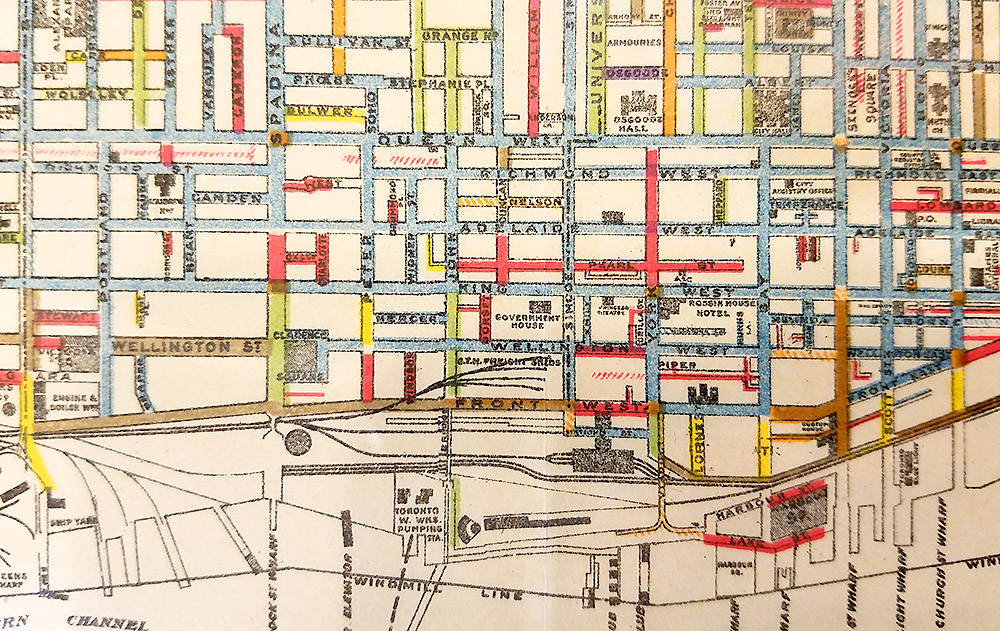

"Plan of the City of Toronto," 1909, using color and hatching to show different types of pavement. (Toronto Reference Library)

Geographic location, economics, availability of materials, freight costs, and even the nature of soils all had an impact on what type of pavement a municipality used and how many streets could be paved. Pavement was expensive, analogous to the huge cost today of installing transit systems. And like transit systems, municipal officials had to decide on the nature, quality and location of the civic improvement. The paving of streets was a highly experimental process and certainly not equitably distributed to all parts of a city. George W. Tillson, a leading municipal engineer, acknowledged the highly localized nature of solving the problem of paving streets in his manual on street pavements published in 1900: “The experience of one city has not seemed to benefit very greatly any other, but it has seemed necessary for each one to work out the problem for itself.” Even with increased communication between cities by the late nineteenth century through official reports, technical societies, and technical journals, he continued, “it by no means follows that the decision as to what is the best paving material for one locality will necessarily govern in another, however intelligently it may have been reached.”[2]

In most cities, the first parts of the built environment to be paved were sidewalks, often with wood planks, flagstones, or brick. Paved crosswalks, sometimes elevated above the level of the dirt roadway, formed the first stage in the process of paving the streets themselves. By the mid-19th century, cities began in earnest to start paving their streets. The first material used in cities along the east coast were cobblestones, naturally rounded stones that were used as ship ballast and deposited on a local wharf as the ship’s hold was filled with export materials. Other early materials included wood blocks – especially the Nicholson Blocks – and Macadam, a type of gravel. Quarried rectangular blocks of stone or setts, commonly called “Belgian Blocks,” became a common paving material during the second half of the 19th century. Granite was most common, though other materials served as Belgian blocks, such as sandstone in Minneapolis and limestone in Hannibal, Missouri.

In 1870, two paving materials had their first use in the United States – asphalt in Newark, New Jersey, and vitrified brick in Charleston, West Virginia. Asphalt initially was a quite expensive approach to pavement and, being porous, absorbed horse urine and droppings, necessitating expensive and frequent street cleaning. Until asphalt became the principal pavement type in the 1920s, when it began its reign as the pervasive material of choice, vitrified bricks would become the dominant paving material in most cities and the historic paving material most likely to survive today. The high cost of shipping bricks, however,

Concrete made its appearance in the 1890s. One of the interesting issues with concrete is the variety of aggregates employed. In Savannah, for example, some streets use concrete with baseball-sized granite aggregate, while other streets have concrete with oyster shell aggregate (not to be confused with traditional tabby, which uses burnt oyster shells for lime).

As Clay McShane notes, “by 1924 municipalities had paved almost all urban streets.”[3] By the 1920s, asphalt would become the pavement of choice, as horses were quickly disappearing from the American cityscape with the ascendance of the automobile. McShane has authored the best scholarship on the topic of street pavement. My own research builds on his work.

[1] Annual Report of Herman Myers, Mayor of the City of Savannah, for the Year Ending December 31, 1896 (Savannah: The Morning News Print, 1897), 13-14.

[2] See George W. Tillson, Street Pavements and Paving Materials. A Manual of City Pavements: The Methods and Materials of their Construction (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1900), 136.

[3] Clay McShane, “Transforming the Use of Urban Space: A Look at the Revolution in Street Pavements, 1880-1924,” Journal of Urban History V (May 1979): 279.